Written By

Yuhong Sun

Published On

Feb 17, 2026

Lessons from building the best Deep Research

(and how you can build better agents)

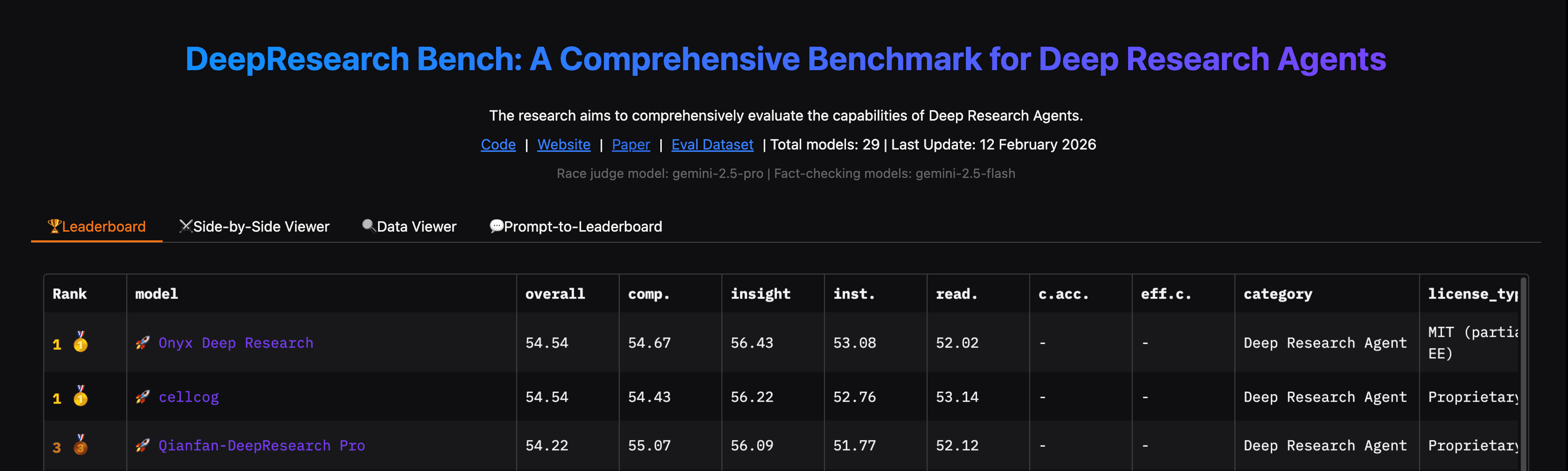

We recently achieved #1 on Deep Research Bench. Through building this system we gained a ton of insights which can be applied to building Agents in general.

Being open source means we get to build in the open, so here are the details that actually made a difference. I'll start with high-level best practices, then get into the weeds for those who want it.

Lesson 1: Agents are just prompts

People tend to glorify what an Agent is, but really–under the hood–it’s just a text prompt! This is an important mindset to have when building LLM-based systems. Your one and only job is to optimize the prompt for:

- A clear, simple, and well-defined task

- All necessary information to do the task

- As little noise and distraction as possible

You want to make the LLM’s job as easy as possible and abstract away distractions, tangential decisions, and anything that isn’t the core, simple goal.

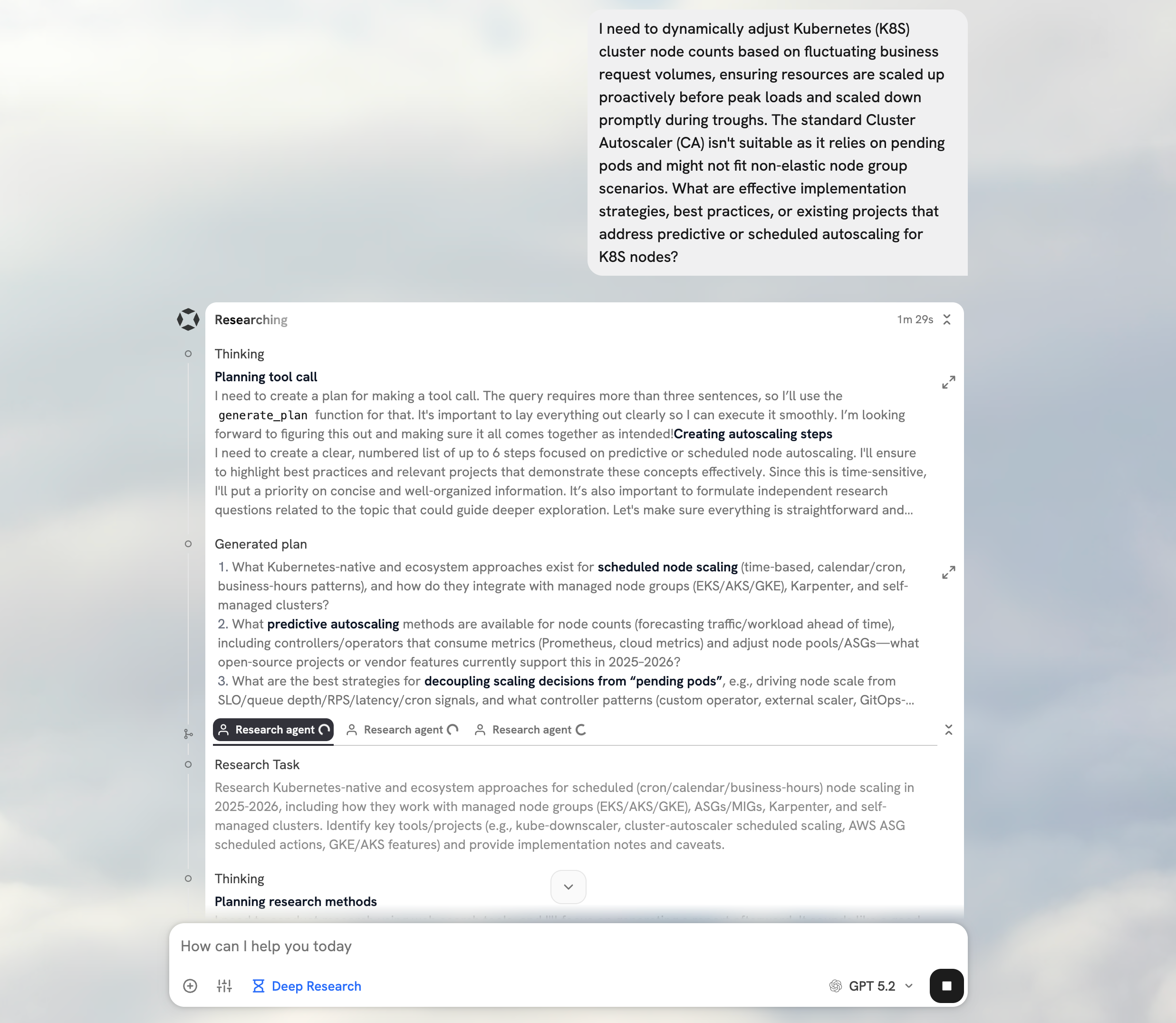

For example, in our Deep Research, we start with a task of analyzing the user’s request and developing a comprehensive, high-level plan. This exercise is completely isolated from the actual execution of the research. We use a specific system prompt, curate the conversation history, and provide examples of plans that are thorough yet digestible by subagents with less high-level context.

The planning task is well defined, simple, and gives us the ability to provide very specific reminders (more on the importance of reminders later). Once the plan is ready, it is the only context we bring into the research phase.

Contrast this approach with instructing the LLM to first generate a plan then immediately execute on it. The task becomes more complicated, multi-step, and the instructions on generating a good plan only act as noise for the later steps.

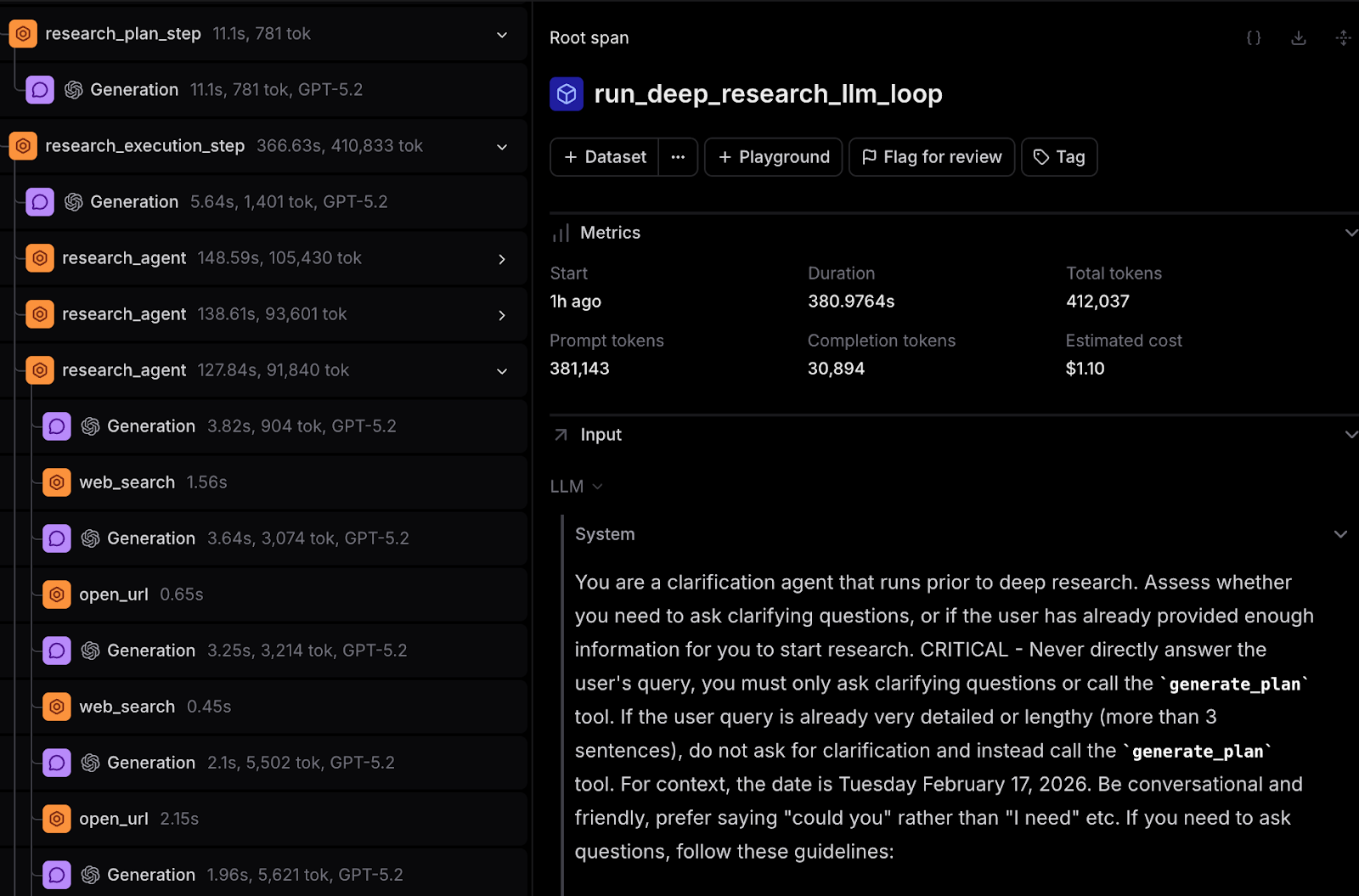

The main loop of our Deep Research is the Orchestrator Agent. It sits at a high level, has access to the plan, and delegates smaller research tasks (as tool calls) to subagents. The Orchestrator basically asks questions and then analyzes subagent reports. This approach allows the Orchestrator to monitor progress and results from a high level without attention to how the research is accomplished. This also means it can make high level directional changes fairly easily.

Our implementation stands in stark contrast to OpenAI’s approach to Deep Research. OpenAI trains LLMs for many, consecutive tool calls, which offloads some effort in orchestrating behavior, but ultimately results in poorer deep research performance (see benchmark). OpenAI’s models get stuck in the weeds more often than not.

At the end of the day, our Deep Research is relatively similar to Anthropic and Google’s. By simplifying the tasks and minimizing extraneous information, we can optimize the prompt at every step and build performant agents that don’t get bogged down.

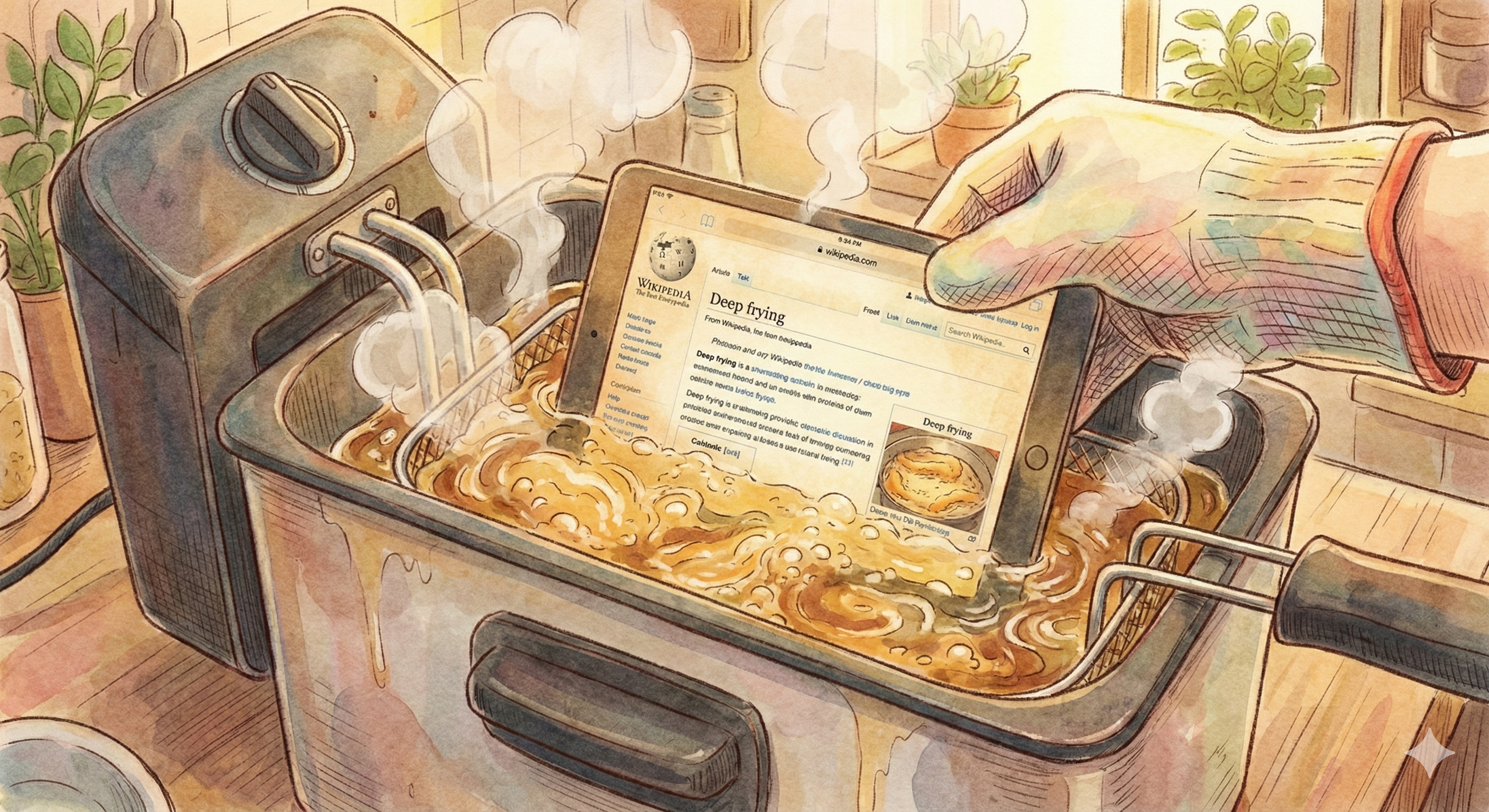

Lesson 2: Deep frying is unhealthy

While experimenting with multi-agents, nested loops, and various approaches to decomposing complex tasks, we observed a phenomenon I’d like to dub “deep-frying.” Essentially, a piece of ground truth information, when relayed through a chain of agents playing telephone with one another, can easily become unrecognizable through just a few layers.

Because of this phenomena, we explicitly avoid deeply nested loops and complicated architectures of agents sharing context with one another. We’ve found that these systems are finicky and prone to breakages.

We call our main loop the Orchestrator Agent, but I want to be clear about how simple it actually is. The Orchestrator just gathers context. It doesn't meaningfully transform or reinterpret information. The subagents are equally shallow. There is a separate loop for research-agents, but the nesting stops there. The entire architecture is only 2 levels deep (never deep fry!). You can see a parallel with Claude Code, which can spin up agents to research a coding task or update the status of a plan, but it's never deeply nested either.

Lesson 3: Leverage LLM Architecture

LLMs are all Transformer based nowadays, which means understanding how they work can directly shape how you build agents. Here are some rules I've devised based on LLM architecture.

Rule 1 - Co-locate instructions

LLMs can attend to any part of their input during generation, but in practice, if the details of a task are split up with unrelated text wedged in between, the model will struggle to piece them together. Let me give a concrete example:

You are a helpful assistant. You use tools to help you find the answer, do not give up and keep using tools until you can answer the user request.

Make sure to use emojis to make your responses more engaging.

# Tools

Here are your tools and how you use them...

Not good! As this prompt grows more complicated and more context is added, the LLM is likely to bail on the exhaustive tool use instruction and forget the emojis reminder entirely.

You are a helpful assistant. Make sure to use emojis to make your responses more engaging.

# Tools Here are your tools and how you use them...

You use tools to help you find the answer, do not give up and keep using tools until you can answer the user request.

Good! When the LLM is deciding whether to use a tool, you want the instructions encouraging further tool use to be right there, adjacent to the tool definitions, not separated by unrelated style guidance. You don't want the model to have to "hop" over response formatting instructions to access all the bits about tool usage.

This simple trick was, very surprisingly, a step function improvement in not just Deep Research, but the entire system. You'll also find it works reliably across all LLMs and isn't specific to any particular provider.

Rule 2 - Don’t add too many instructions

This one is a bit more provider-specific. Shoutout to Anthropic! They handle this better than most, but even they acknowledge that sometimes too much is too much.

https://www.anthropic.com/engineering/effective-context-engineering-for-ai-agents

The tasks you give the agent should be high level, and the finer instructions guiding it should be just a cherry on top. If you have too many instances of "in this case do X, but if it's like that, do Y," LLMs lose track very quickly. You also run the risk of the majority of these instructions not applying at any given moment, silently degrading the experience. LLMs don't perfectly skip over irrelevant tokens. A lot of these instructions will get pulled in at the wrong times, contributing noise to the task and leading to weird artifacts.

For example, we instructed the LLM to always respond in the language of the user's query. Occasionally it would respond in Spanish—even when all the instructions were in English, all the documents were in English, and the user's query was in English. These artifacts also reduced when we simplified the prompts to contain fewer specific instructions, and even when changing lines completely unrelated to language.

An example of an “artifact” from Google Gemini (Node 6, 7, 8 etc.)

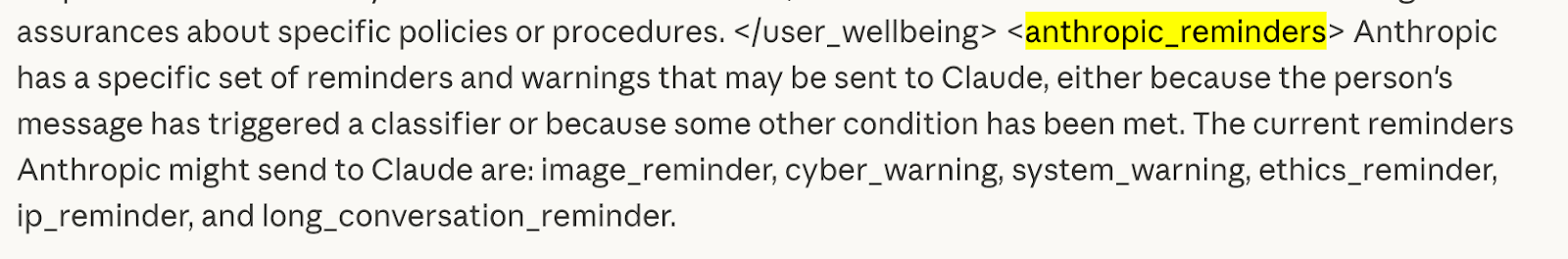

Rule 3 - Use Reminders

There isn’t a huge amount of literature on this but all the best products are doing this behind the scenes.

From Claude’s System Prompts:

In the OpenCode repo, you can just search for <system-reminder> to see how extensively they use reminders.

In a nut-shell, reminders are text prompts that the system injects at the very end of the context passed to the LLM.

This works because when generating new tokens, the LLM always attends very strongly to the most recent tokens in its input. This behavior feels relatively obvious, but very few people actually implement it in their agents. We discovered this around late 2023 when trying to get GPT-3.5 to reliably produce citations. At the time, we benchmarked it at around 70% reliability without reminders and around 99% with. Nowadays this isn't needed for every task—especially when the context is short—but for anything that requires reliability, I strongly encourage it.

One more note: this is also why having simple tasks matters. Reminders are ideally short and coherent, meaning they're asking one thing of the model. For example, in our research-agents, one of the reminders is:

<system-reminder> Remember to provide inline citations in the format [1], [2], [3], etc. based on the "document" field of the documents. </system-reminder>

Lesson 4: Tool Design

Designing the right set of tools, and making sure there aren't too many, is just as important as everything I’ve mentioned so far. There's a lot to cover here, so I'll use web search as an example.

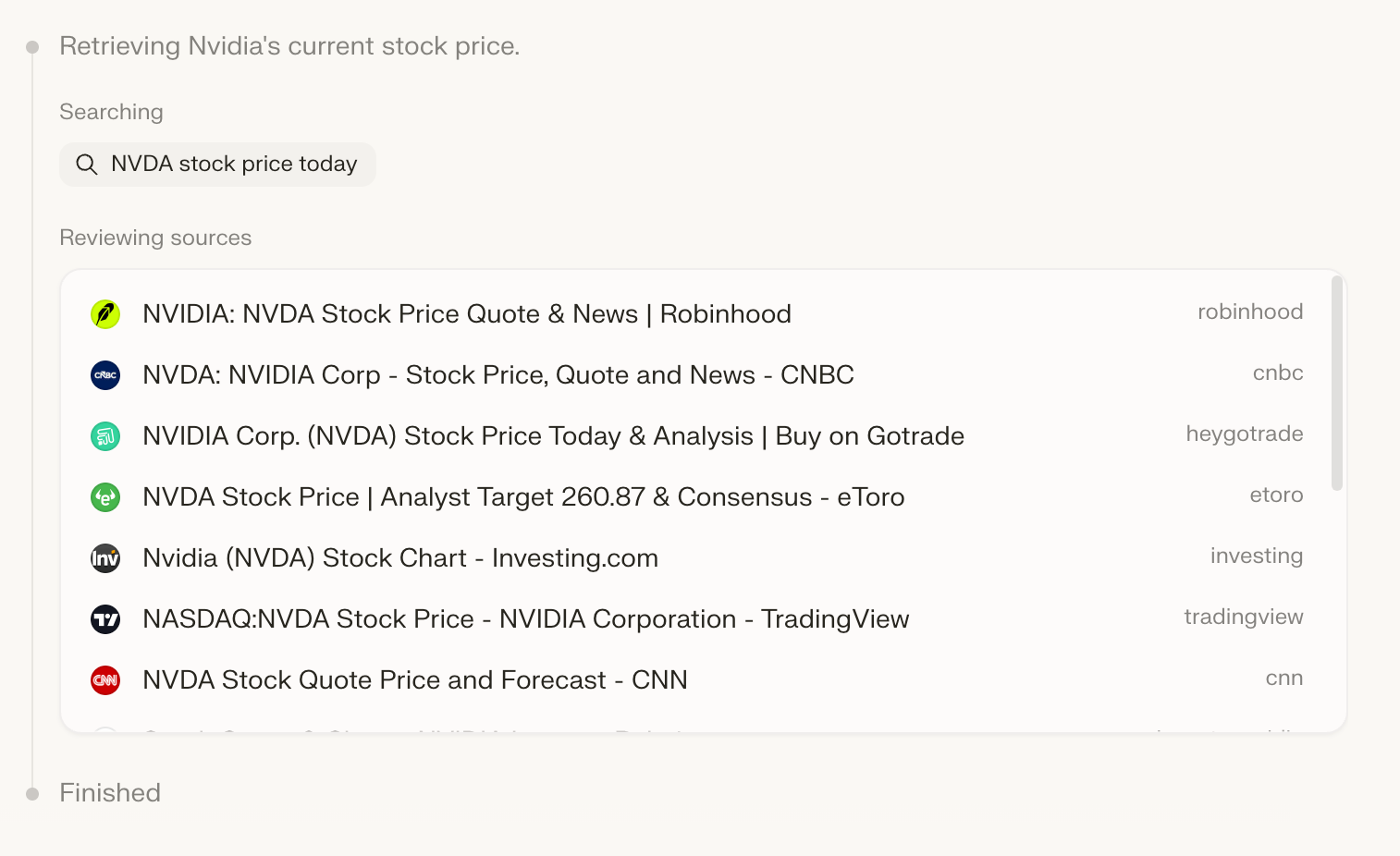

Side note: if you're building functionality that isn't unique to your system (like searching the web), it pays dividends to see how others are doing it first. For web search, nearly every large system has converged on the same paradigm (Grok, Gemini, ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity, etc.).

In a previous iteration, we had web search as a single end-to-end flow. Fetch results, expand the highest-ranking ones, and pass them to the LLM. But this takes away the LLM's freedom to decide which results are actually most relevant based on its own context and knowledge of the sources.

Other implementations (such as LangChain’s open_deep_research) use LLMs to summarize web results with respect to the research agent’s task. This helps weaker models by reducing noise and making search simpler. But it handicaps better models since the research agents lose access to ground truth:

- The summarizing step isn't aware of the other results and might throw away novel findings just to repeat something found in a prior step.

- Facts become disconnected from their sources, making it difficult to resolve contradictions and filter out questionable origins.

For Deep Research, there are also steps where reasoning capabilities can greatly improve quality. To support non-reasoning models, we added a think_tool, a chain-of-thought approach that predates reasoning models. That said, we strongly encourage our users to use reasoning models, which are fine-tuned to optimize this through more than just prompting.

The takeaway: your tools need to be optimized for the LLMs you actually want to support, or at least the right size and generation of model.

Onyx Deep Research from 1000 feet

- Clarification Agent: runs in the beginning with a custom prompt and access to the chat history to determine if there are any helpful questions to ask the user

- Planning Agent: comes up with a high level plan of attack to cover all angles of the user query. The system is given flexibility based on findings but this provides a scaffolding.

- Orchestrator Agent: is the main loop which delegates lower level research tasks to the Research Agents. Its only options are to call `research_agent`s or to call `generate_report`.

- Research Agent: sub-agent loop, which has access to search related tools like `web_search`, `open_url`, `internal_search`, and `generate_intermediate_report`.

- Intermediate Report Agent: Generates a report with citations for all the findings of the research agent.

- Final Report Agent: Generates the final report for the user at the end of the day.

- Then finally there is a lot of scaffolding and edge case handling like injecting reminders at different times and given different states of the history and tool calls.

Closing words

To summarize: don't overcomplicate agents. Treat them as context and prompts, and make the LLM's job as easy as possible. Keep context management simple, ideally a linear history without too many modifications. For more complex tasks, a layer of abstraction between agents can help, but don't overdo it. Most real production systems never go more than 2 layers deep, and for good reason.

If you like in depth and actionable advice in building agent systems, you can also reference this README which explains the main agent loop in Onyx and the motivations behind it.